A.I. Will Replace Us (Writers, That Is)

This Week's Short Takes • The Whole 'Nuther — Vol. 2021, No. 7

Who Needs Writers?

Stephen Marche recently explored advances in the field of artificial intelligence that may soon marginalize the profession of writing. Computers, he found, are getting better and better at it, though they don’t yet quite know what they’re saying. Still, for all practical purposes, we’re not all that far from a time when a company that needs, for example, someone to churn out some copy about how to use its latest product, will be able to feed basic information into a computer and have it produce instructions that are as good as any human technical writer’s work.

That may not be all bad. If you’ve ever tried to wrestle with the pseudo-English instructions accompanying many products made in China, presently written with the help of Google Translate, anything would be an improvement.

But what about creative writing? Will such software be bad news for thriller writers and crime novelists, who already follow formulas? How about literary writing?

Marche tried out some of the software by feeding in a sample of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (a novel about the existential problems of Gregor Samsa, a man who wakes up one day and discovers that he’s a giant cockroach), and asking the computer to continue the story from the point where Gregor’s father kicks him, bleeding, into his room. Here’s the result:

As soon as Gregor was alone, he began to feel ill. Turning around was an effort. Even breathing was an effort. A thin stream of blood trickled from his flank down his fuzzy belly. He wanted to crawl away from it, but there was no place to go. He lay still on the spot where he had come to rest just in order to get his breath back and to stop the bleeding. “I’m in a bad way,” said Gregor. It had never occurred to him before that he could really become ill. He had seen sick animals—a dove once in a while, which had fallen out of the nestling into the gutter and could not fly any more, or the weak infants of the woman next door who had to be picked up with the tongs and thrown into the dustbin, or the bugs his father used to bring to him when he was still a young boy and which he had liked so much.

It’s kind of scary. That’s a pretty interesting paragraph, though if you read carefully there are a few elements that fall into the so-called “uncanny valley” of weirdly inhuman computer imitation.

And what about journalism? Will computers report the news, slanting it according to the data they’re given?

Political rhetoric is already halfway there. If you spend much time watching Fox News, for instance, you soon realize that a lot of the TV personalities and hosts are basically humanlike robots being fed the latest talking points from the control room; their job is just to add a little personality to the ideas and to deliver them clearly. But in print, there’s no need even for that human illusion. It will soon be perfectly possible to feed in ideas and have an A.I. program spit them out as lively, polished prose.

Will anybody be able to tell the difference between that and current right-wing trolls on the internet? Is it already happening? Calling Sarah Connor!

Word Hoards

Back when I was trying to pass a grad school exam on the Old English poem Beowulf, I crammed using a book called Word Hoard: An Introduction to Old English Vocabulary.

Old English, if you’ve never run across it, is our language’s German grandfather, spoken from about 600–1150 AD, and Word Hoard was a utilitarian text meant for students in exactly my situation. “Wordhoard” is an actual Old English word, one later made obsolete by the Latin-derived word “vocabulary.” It describes the words a person (or a poet) knows and draws on: Him se yldesta andswarode, werodes wisa, wordhord onleac, the Beowulf poet declaims—“The eldest of them, the troop’s captain, answered him, unlocking his wordhoard.”

Man, I’m glad I won’t be tested on Old English again.

I thought of it this week, though, when I read Barry Yourgrau’s funny 2016 article, “On Writers, Hoarders, and Their Clutter—From Auden to Mitchell: Messy Life, Brilliant Mind?” Yourgrau linked back to it on the occasion of writer Janet Malcolm’s death. Malcolm had corresponded with him, and described the apartment of a hoarder she’d interviewed about Sylvia Plath, his neighbor, in this way:

“on every surface,” she reported, “hundreds, perhaps thousands, of objects were piled, as if the place were a second hand shop into which the contents of ten other second-hand shops had been crammed . . .” And all coated with dust “overlaid with dust.”

I’m not convinced by the wishful thinking of Yourgrau (who depicts himself as a hoarder seeking to mend his ways and hoping for literary success) that there is actually a correspondence between the jumble of junk in a writer’s study and the idiosyncratic wordhoard in the writer’s head. In the article, though, he goes searching for “a literary fellowship of clutterbugs.”

The poet W.H. Auden, a notorious clutterbug, but possessor of an astounding wordhoard, once complained that “we make a scarecrow of the day/ Loose ends and jumble of our common world. . . .” But that poem, “Canzone,” about the messiness of life, also asserts that it’s part of being human: “we are required to love/ all homeless objects that require a world.”

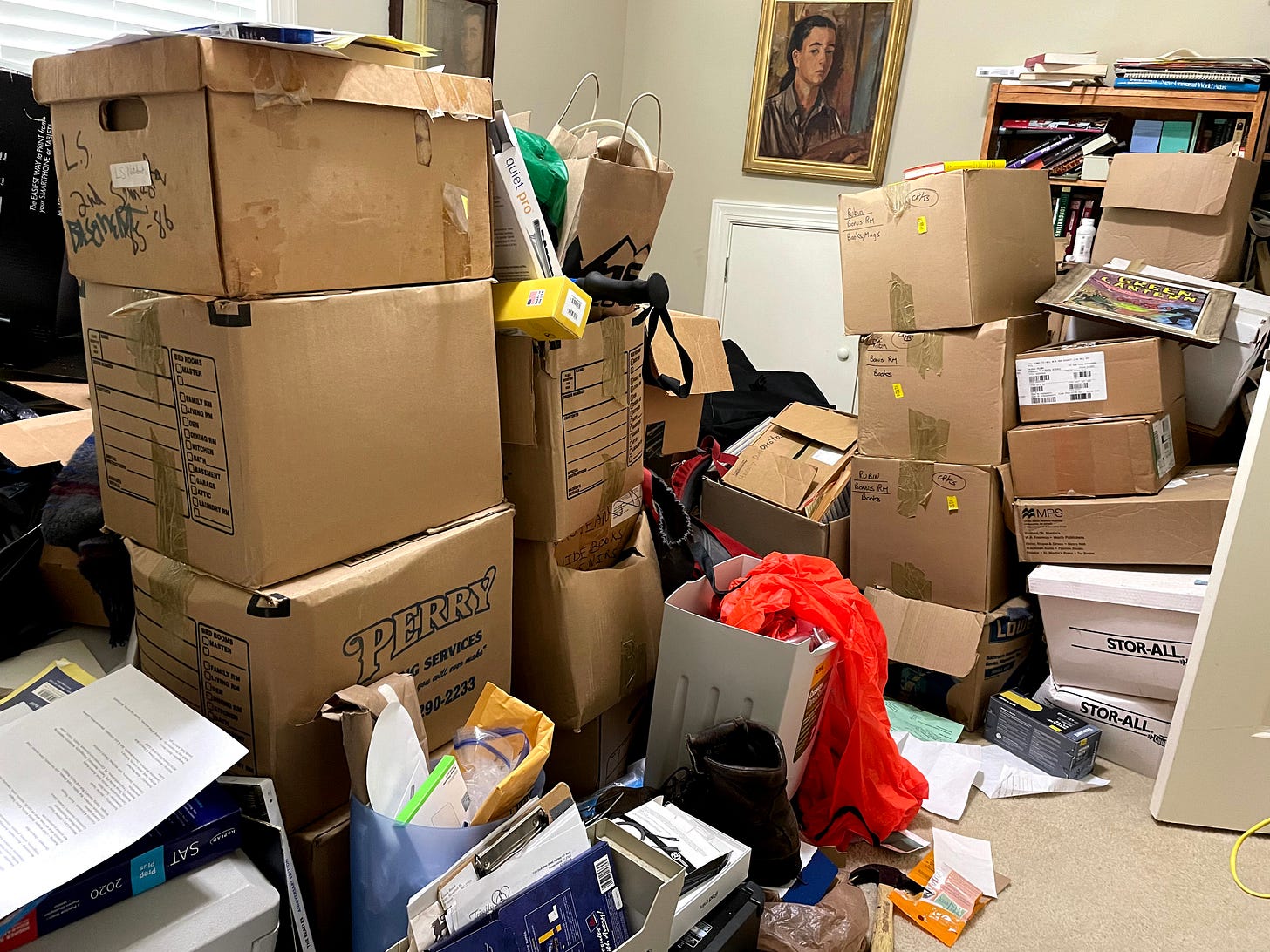

So maybe there’s still hope for me. We recently had to clear out part of our attic, where I’d stored boxes of old books, so that electricians could get in for renovations. The boxes went into my study, where I promised to sort through them and weed out the books I’d never need, or read, again. That was a few months ago. They’re still there, with other stuff, including hiking gear, piling up around them.

I will get around to unlocking this wordhoard shortly:

þa se eorl ongeat þæt he in niðsele nathwylcum wæs, þær him nænig wæter wihte ne sceþede, ne him for hrofsele hrinan ne mehte færgripe flodes.1

Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf’s entry into the monster Grendel’s lair reads, “The gallant man could see he had entered some hellish turn-hole and yet the water did not work against him because the hall roofing held off the force of the current.”